4 Klaus Thomsen

Coffee Collective

To evade the so-called coffee paradox, four coffee enthusiasts set out to form the Coffee Collective in 2007 in Copenhagen. Hear how co-founder Klaus Thomsen built a sustainable business with a mission to create the best coffee experiences in the world while bringing better returns to the farmers.

Klaus belongs to a new generation of entrepreneurs taking a stand and inspiring others to improve the coffee industry collectively — one bean at the time. In this episode, we talk about purpose-driven profits, transparency from seed to cup, and continued investments in the company culture for future growth.

Silja: For today's episode, we joined Klaus Thompson, co-founder of Coffee Collective at their Copenhagen based roastery. He's in charge of marketing and responsible for the coffee quality across there four locations. After more than a decade of non-stop commitment to coffee and farmers, Klaus belongs to a new generation of entrepreneurs striving to balance purpose and profit. Sounds easier said than done. So we asked: Isn't there a quicker way to make money than changing a whole industry — bean by bean?

Klaus: Absolutely. Making money was never even the slightest motivation for us, the founders of this company. We were basically three (at that time young) guys who'd been working in coffee for a number of years in the same company. It was called Estate Coffee. It was a founded by - I'd say probably the most famous Danish Food entrepreneur especially in those years - Claus Meyer who has done tremendous things for Denmark as a whole in terms of food and discovery of things. And we were working in different departments in that company. Peter, who's one of the co-founders, Peter Dupont, he had actually opened their first coffee shop. I think when was that? All the way back in like 2000 or something; like quite early on. One of the first coffee shops in Copenhagen. And he had become a partner in the roastery that they had opened in Valby, a part of Copenhagen. So he was running the roastery. I was running the coffee shop, basically taking over Peter's job and then Kasper, who is the third co-founder, he was in their wholesale department; selling coffee to other companies.

Simon: So you knew each other before then?

Klaus: Yeah, we knew each other and were like we were doing a lot of things like I was in these coffee competitions. And Peter especially was a huge part of my training and my team around that. And Casper was also a big part of it, and very sort a young and energetic. And so we were in these three different departments, and we kind of were really coffee geeky, I would say. We were spending a lot of times, you know, outside job as well like investigating coffee, meeting up, tasting, brewing; all these sorts of things. And then I had won the World Barista Championship with Peter as my main coach and that had sent me travelling all over the world from Tokyo to Seattle to Cape Town — doing talks on coffee. But for me personally, also learning a lot about coffee in different cultures. And I'd set up my own little private company doing these talks and events. And while I was doing that I felt a little like lonely as well because you're giving talks and you're not getting a lot back, and you're kind of like you know you're out there, but you're not getting pushed either. You're not getting questioned. Nobody calls you out on your bullshit. So I was kind of missing like a more tight group of people to work with. And at the same time, Casper, Peter and I started talking about all these things in the coffee market that we felt could be a lot better than it was. We felt that like overall when you looked at the coffee markets, we felt like something was terribly wrong. We had this experience in that company and looking at the market that there was a lot of producers out there producing amazing coffees yet they weren't getting paid very well.

Silja: Did you visit them already back then, or how did you get to know the farmers?

Klaus: Yeah, we were spending time at the origin. And actually, when I took over his job at Estate Coffee, Peter had gone to Nicaragua to write his Master's thesis on the water wastage from coffee farms. So he'd spent, I think, four months in a small but very famous coffee-producing town in Nicaragua and there he'd really seen the everyday life. Living there, he was really standing out in the crowd there — from Denmark. But he'd really seen sort of what actually is the reality of coffee farming. And so there was a lot of experience there. He was studying International Development and Biology. Wastewater Management. So he was really into this: What is the reality there? How can you be part of developing these poor areas as well? So that became his experience. And it became an integral part of forming our ideas and about the company in general. And so we sat down and looked at this market. It was at the end of what was dubbed, the coffee crisis. It was a crisis that is actually being repeated today, where farmers were getting less than the cost of production for coffee. At the same time you know we were looking at, you know the markets in Europe where Starbucks was expanding like crazy, and it seemed like coffee consumption was really getting traction. It still wasn't big in Copenhagen, but we as baristas could tell that: Hey people are really into this. Like it's not a niche product, it is actually a lot of people who find it exciting. And so there was a consumer willingness to pay a premium price for coffee. The prices for a cup of coffee in the high streets of Europe were getting insane at the point. There was so much money. At the same time, as farmers are not getting paid even the cost of production. So that was completely absurd. It's a complete paradox that you have so much money, and yet farmers aren't being paid well. So we sat down. We started talking about this and said: Well, we can change that paradox around. If we can take control of this situation, we can actually say that there's no excuse for not bringing value out to farmers. We can build a better model. So we get the money that is coming in from the customers willing to pay it. We can make sure we get it out to the farmers.

Simon: How did you identify these levers for doing so? I mean there are probably hundreds or thousands of possibilities to do so, but how did you identify these …? Because I think transparency is one of the key actions you do and doing since then, I think. How did you end up with transparency?

Klaus: Yeah, I think we could see immediately (from the get-go) that if we are transparent about what we bring out to the farmers, and we pay them well, I think it came back to us having that appreciation as baristas that when we talk to customers, we could see they were really into the sustainable parts of the business. They were into not only learning about the history behind the product. Storytelling was this big marketing concept that was up at the time and coffee was always used as a fantastic example of storytelling, and I felt half the time it was just pure bullshit because it was just about telling a story to make it romantic. We felt like "no, no, no“ it has to be the real story behind the product and if it is real and if you can back it up until that well the farmer's actually gotten good value for this coffee. You could just tell by the look of the eyes of the consumers that they were into it. And so whenever people said like: Ah, you know, consumers don't care. We had just the complete opposite experience. And that made us believe that "no, no, they're wrong and we're right in this". Customers do care. So transparency was a way of saying well if we're transparent about what we do it makes it easier to communicate all this. We also felt that there was a necessity to go visit the producers every year. Estate Coffee was actually buying some of their coffees in a similar model. They were buying it directly with some of the coffees. Some of them, they'd been visiting the farmers. But we'd also seen some issues that they weren't doing it with all coffees, first of all. That made the communication to us a bit unclear. And I still think that's actually a huge issue in the industry today that some roasteries will do it with one or two coffees. And then it's almost a little bit like greenwashing because you can always point to those coffees as "oh we have this direct relationship", and then you're buying 90% of your coffee through a broker who's maybe buying it through several steps. And along the way, you lose the transparency. You lose the overview and if that portion of the money (that you paid) actually went to the farmers. What can you guarantee? So we wanted to make sure that we committed 100% to it.

Silja: And that is also the term direct trading?

Klaus: Yes. So we came up with this term, or we actually borrowed the term from some roasters in the United States that we started talking to because we could see they were doing something very similar to what we were planning to do. A very famous coffee buyer called Geoff Watts had actually written a blog post where he was like telling these principals, that they were working for at their company, named Direct Trade. And we were looking at this and said: Hey, this is all the stuff we've been talking about but also with some different nuances. They wanted the farmers to commit to certain vague practices in terms of social responsibility and so on, but they weren't really defined. But we said we don't actually want to demand anything. The only demand here is that it is on us as a roaster. We don't get to ask anything from the farmers until we commit to paying a high price. And so we used that term Direct Trade because it was very clear. It put an idea in people's head that it's direct and there's something about trade. And the idea was not to make it a big certification, but it was to make it something where people would be interested in: What is that? And you would have an access point for dialogue; a touchpoint where people would hopefully ask more questions about what you're doing.

Simon: And you said, setting the price right in your senses is that the farmer actually could make a living?

Klaus: But more than that because I think that's what Fairtrade does. Fairtrade sets a minimum price that should basically be like the lowest price anyone could ever pay for coffee because below that price you can't really make a living as a farmer. But when we're talking specialty coffee, we're talking coffee that requires more effort from the farmer for us to achieve superb flavour in the cup. That requires far more than that. So we wanted to negotiate prices directly with farmers based on the quality that they produce. So that we can look them in the eyes and say "I think, you made something extraordinary here". This tastes amazing. I don't see any reason why consumers in Denmark shouldn't pay a really high price for this coffee so I can pay you really well.

Simon: If you look at your packaging: On every bag of beans, you write the percentage of how much you paid more for the green beans to the farmer. Do customers have questions about that or do they just love the transparency? Or how does this, you know, come across the customers?

Klaus: Mostly, it comes across as again a touchpoint; a starting point where it doesn't explain much on its own, but it does say something about "well, wait they're actually willing to show the price". I mean imagine you went into a clothing shop and you looked at a shirt and see the cost of production in the shirt. …

Silja: You'd probably be surprised.

Klaus: Yes, you'd probably be pretty surprised. And to any clothing vendor, it seemed like that's suicide for your business if you start doing that. And so people thought it would be the same for us like showing all the prices people are like well aren't people going to say like why are we paying this much when you pay this.

Simon: How much is it actually? Let's talk about money!

Klaus: I mean it's, ah I'm so bad with the actual numbers. I mean the price we pay over the market price will easily be 130% and sometimes it's like 480%. So it's so much more than the market price. Still when you look at a bag of coffee, and if you start doing the numbers, it seems like little. It's a big gap from what we paid to what you as a consumer pay. But here's where I think it gets really interesting is that again we have so much faith in customers because we know that people can see through. They know that. Yeah, of course, it costs less for us to buy green coffee. And maybe they don't know that, but there's like 20% roast loss like from the green coffee weight to roasted coffee. There is a lot of evaporation of water so waste less. Of course, they know those expenses to gas to packaging to salaries all these things. So I think it actually is not that like we've actually been surprised we never had any bad criticism where people have gone where this is the cost, and you're charging this? On the contrary, we only had positive responses: People saying like "wow, I'm impressed that you were so honest about it". Because it is an industry that is, you know … you can pay the same price for a bag of coffee as ours in a number of places. Even the supermarkets have coffees that charge the same but have zero transparency.

Simon: Right! And they buy their green beans for less than a dollar per pound.

Klaus: Exactly. Yeah. Well, we are buying some of ours at 6$ per pound to put into perspective. Yeah. And even like our most expensive coffee is 50$ per pound. So like that's, of course, the extreme but it's to showcase again like that is the difference. And it's interesting; we often get compared to wine and other products and in wine. Yes, you can buy really cheap wines but if you do that you kind of know what you're buying. You're probably not going to sit with a glass Saturday night and swirl around. You're going to put them into a sauce or something. But any consumer, even the ones who will buy the cheap wines they know that there are wines out there that are so expensive and they know this like something worth paying. And I think that's where we finally get into with coffee that we didn't have the first many years of our business. But this appreciation that there are finer coffees out there that are really worth paying for.

Simon: You touched upon the cost of not only producing but also having the staff costs, which are exceptionally high here in Denmark and Scandinavia as well. And I think 90% of your gross profit goes into labour costs. Why Denmark then?

Klaus: I mean just because we are from Denmark. All four of us that originally founded the company or the three of us actually … we had a fourth member when we founded the company. He was Swedish but moved to Copenhagen, and he left two years ago to move back to Sweden. But the three of us are from Denmark, and we feel at home here. Like Copenhagen is a fantastic city. At the time, it was just where we were. And now it's quite interesting to see that Copenhagen has become this like hub of gastronomical entrepreneurship globally which is amazing. That wasn't the case twelve years ago like we never really saw it coming. But I think that whole being part of that like the melting pot of Noma and Geranium and Relæ and all these places doing super interesting things in food. And then Mikkeller and To Øl, you know, exploding people's minds in beers.

Silja: And I also think the whole farmers … What's the term? Ah from farm to table is sort of the same from seed to cup in your way.

Klaus: Yes, exactly.

Silja: So that's a movement as well that you probably benefit from and contribute to.

Klaus: Yeah, benefitting from this excitement about whatever you sort a digest, I would say or whatever you put in your face. And it is quite funny because I remember especially in the beginning people saying like: It's such a small niche with the specialty coffee and the like yeah maybe, but that's fine with us.

Silja: But so many people drink coffee. So that's a huge opportunity.

Klaus: Yes, it's not really a niche. I mean it's like I saw a report once that 94% of Danish households have coffee in them like they have a coffee machine or will brew coffee regularly.

Simon: And the Danes are consuming a lot of coffee compared globally, right? It's in the top 5!

Klaus: Yeah, in the top five or the fourth position every year. So that's not really a niche, and then with specialty coffee as well we were like well even if it's a niche we'll just cater to that niche. We have faith that if we like it, there are probably other people out there who like it too. And the interesting thing is: No matter how you look at it, it's not a niche. There is such a large percentage of people, especially in Denmark and especially in Copenhagen, who are really into food. They're into learning about the history of where the products that they're cooking at home comes from. They're into going to restaurants. They are into experiences. I saw a report earlier this year that said that three out of four people identify themselves as like maybe not a foodie but some sort of person who's interested in what they digest. So that's actually the majority of people. So yeah.

Simon: And I ask about Denmark because you are not selling your coffee just in your shops you also sell them to other restaurants, for example through wholesale. And you also do a subscription service which is available worldwide.

Klaus: Yes.

Simon: What are your plans towards going global? Or do you ship already to many other countries? How does this work?

Klaus: Yeah, we do. When we started out, we really thought we wanted to be a local roastery. We wanted to be Copenhagen-based. We wanted to supply cafes and restaurants around Copenhagen like a local micro-roastery. And that is still like a big part of us to be local be in touch with our customers both wholesale but also the coffee shop customers. At the same time, I remember one of the first (after starting the company) one of the first advise that you're given is that as an entrepreneur in Denmark you have to think outside Danish borders because it is such a small country. And I remember at the time being a little bit like "yeah I don't like that". We just want to be local. And so we focused very much on being local. And then I think just by popular demand like people writing us from abroad and really wanting our coffee we slowly started growing outside of Copenhagen and outside of Denmark. From the beginning, we opened a webshop just because we kind of felt like well if you're in Jutland (Denmark) and you want our coffee you should be able to order it. And so it was really for the Danish market. And that webshop just slowly started growing and got more and more international.

Simon: When was that?

Klaus: That was throughout, like 2008/2009/2010. And it's since then just grown steadily, and now we're shipping like our subscription is shipping to like I think 46 or 47 different countries around the world. Our biggest market is South Korea, and the United States gets a lot of coffee. And wholesale as well as grown like we're shipping coffee to Japan. And you know, all over the world. We mostly tried to focus our efforts on Northern Europe because it's closer to home. But it's just so interesting to see that because they can't really get what we deliver in these other markets in terms of the sustainability, transparency, prices and the taste quality that we deliver. There's just this big demand for it and yeah we are happily supplying them.

Simon: Right. And is it also a brand game, a little bit? Because if you think about it, Coffee Collective has become, at least in the scene, a very well-known brand I think. And you recently redesigned your brand and did a website and all that. So is this something to factor in?

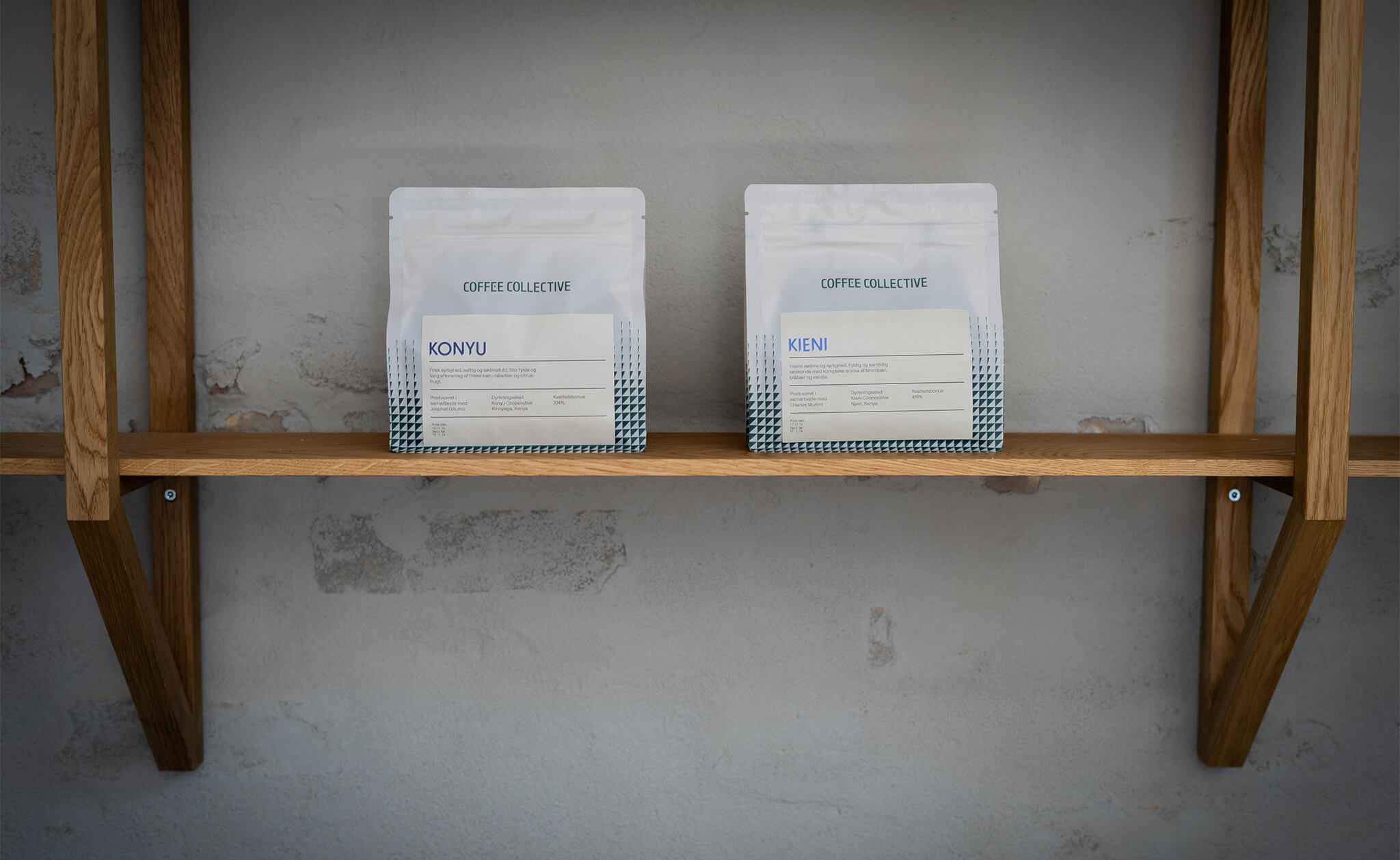

Klaus: Definitely. And I have to be honest I think when we started out twelve years ago it was actually not that common that people had such a coherent branding as we had at the time and it was something that was actually a big motivator especially for me and Kasper in starting the company was that we felt we were both very much into design and into like music and arts and all these different things and we really wanted to create a company where it was like a holistic approach to the experience you had as a consumer. So we teamed up with a branding agency. They were starting up and also four founders who had just started at the same time, and they wanted to use this as a showcase back then. And so we actually came out with this full package that typically roasteries didn't have. Usually, they just had some brown paperbacks and the logo with a coffee bean in it. So we had this long list of what we didn't want. We wanted to be like a fresh multicoloured white bag, all these different things that you didn't see. And since then that has become the industry standard. Like now you'll see micro roasteries who have like the most impressive packaging of any product that I can speak of actually and like amazing brand experience, design and everything before they've even roasted their first coffee. Which to me is maybe like we have to be careful as an industry not overdoing it. We have to be careful that it doesn't become like Swiss chocolate that's just packaging and no core quality in the product.

Simon: Be careful about what you say about chocolate.

Klaus: I know, I'm going to get kicked under the table here. There are exceptions of course, but I think sometimes you just have these products where it's like it's too much branding and packaging and not actually like …

Silja: … delivering the quality.

Klaus: Yes, delivering quality. But we also did the rebranding because out of our own sort of desire that we had some especially with the bags we really had to desire that we wanted to showcase the farmer even more. We wanted their name to be the most visible part of the backs. Like I kind of felt bad sometimes that if you were like standing 10 meters away from a retail shelf, you could just make out our logo but you had no way of making out the farmer name like you had to get really close to see that. And for me, that didn't feel like what we're about. We all agreed that this should actually be a bigger font than our name on the bags. And then we also felt that we just wanted to do something new. We had the same kind of branding for over ten years. And so we thought it was time to show: Well what are we going to look like the next ten years? We've developed as a company. We've grown. We have you know getting more precise about what our values are. So we could get that more into play in our branding as well.

Simon: And you're speaking of it. You're approaching 50 employees around that time. Right?

Klaus: Actually, we're about 70 employees.

Simon: Wow!

Klaus: Yeah, roughly. If you convert it into full-time positions: 45-50.

Simon: And your sustainability reports says also there are 50% male employees. And you're from 10 or more different countries.

Klaus: Yeah.

Simon: And speaking of values, how do you get those people under one hat? How do you communicate that to all of them? How do you keep up that consistent quality across the shops?

Klaus: I think, fortunately, we have a really strong foundation since the very beginning. The company grew out of just us owners doing everything like we were roasting the coffee, we were out wholesaling and we also the baristas in our first coffee shop. So we were standing there next to other people and especially at the beginning you know you'd just be standing next to them every day. So it was like a soft transfer of your values every day, and they would see how we were doing things. And then as we grew, especially when we opened the food market Torvehallerne, we suddenly tripled our amount of staff, and it really was a big change going from us being next to them to suddenly not being next to staff all the time. And at that point we really invested heavily in and over the coming years we invested heavily in building the structure that would ensure that the values, the way we do service, the way we talk about coffee, the way we share knowledge became an integral part of the business. And we've spent quite a number of years instead of just opening new shops building on that backbone building on what are the systems inside the company that will support that for future growth. But also because we are in an industry where we have really good staff retention but still we know we have a lot of young people as well who come in and work here for maybe a year, and then they want to study, or they want to travel or something so there is a natural shift that will always be in this profession in the service industry in general. So we really have to have a system where people get the level of education that we want and they get to the quality level in their craftsmanship that we demand relatively fast. But also that if there are people who want to stay with us that there is room for growth; there's room for staying here; there's room for a building on your skill level and growth. And it means that we have a number of staff members who have been here for many many years. Some of them are approaching their tenth anniversary in the company, which is incredible to think of. Because typically it's an industry where …

Silja: … you have a huge turnover!

Klaus: Yes, huge turnover and you know you have a lot of people looking at the baristas and saying "oh, when are you going to get a real job?" Which is so idiotic to me because this is a real job. This is actually a really good career opportunity to work in something that provides value to yourself on more levels than just making money and something where you get to work with people, and you get to work with a super interesting product.

Simon: We were talking about the values, and you opened your fourth shop. I think last year or two years ago?

Klaus: Yeah, I'm also in doubt now.

Simon: And of course, I have to say we are terribly biased because we tried every one of them multiple times maybe once a week or something like that. But what surprises me, what really struck me is the consistency of the quality throughout the years and every single time. And I think that's unique because from my experience a lot the quality comes from the barista as well and you know if every step of the process got right, you then get the proper quality. Are your demands so high? Or what is the secret behind that consistent quality? Especially with a product that is living, right? Coffee is not a dead product. You can't deliver like on a thousand unit basis. You have to get it right every time.

Klaus: Yeah.

Simon: How do you do that?

Klaus: So I think one of the first things is that we really think about the whole coffee chain very holistically. The reason for the name Coffee Collective is because we see it as a collective effort. Like you can't just single out one part of the chain and say that's the important part. I see some roasteries thinking that they're the important part, but you know they're 100% dependent on whoever brews their coffee. They will never be better than how it was brewed at the same time they are never any better than what the farmer that they bought coffee from has delivered to them. And so we tried not to get sucked down the rabbit hole on one little aspect of it but rather to try and look at everything from seed, involve ourselves 100% with the farmers in how they produce the coffee, take charge in everything from processing to shipping to how we store it in Denmark, then obviously how we roast it, geek that out completely and in quality control every single batch that we roast but then deliver it all the way down to the level where you experience it to the actual cup. And I think, which is not a secret, but I would say the secret sauce to the company is probably that we started as baristas. We have worked the floor for so long. We have that intrinsic appreciation of how hard it actually is to be on your feet eight hours a day serving customers. It's tremendously fun. It's also really stressful at times, and it demands a lot. And it's not for everybody to do that work but we have to appreciate how important it is and we know that if they don't deliver on it, all these steps like the hundreds of peoples of work that has gone into the coffee before it reaches the cup that's all lost if that person, in the end, isn't brewing it with the utmost attention and isn't serving it in the best possible way creating that experience that will lift it. So I think that goes into everything that we are not just you know we're not just founders in the way that we're investors or we had this great idea about starting a coffee business. And I think that's where it goes wrong for a lot of companies that they just see this staff changeover as something that's super annoying. A lot of them feel like it's pouring water into a bucket with a hole in because they're just leaving again. So why do we spend so much time training the staff if they're just leaving? Well, we see it completely differently. We see this as the most important part in delivering the quality and we don't see them as something that's expendable like we don't see that's just people who are in and out or you know we really have a lot of appreciation of the work they do and want to create the best work environment we can. And also to you know a lot of them are young people who are here in very formative years and so give them a good experience. And hopefully, when they leave, they had you know great years with us.

Silja: You inspire people. It doesn't matter if it's the farmers; if it's the customers; if it's the baristas that you work with or that are working in other places. Is this collective way of seeing your business the only way to sort of save coffee or the coffee industry?

Klaus: So that's a big question because when you look at the whole coffee industry, specialty coffee as being the premium quality is still a small segment of the market. And the way we work, I think actually yes. I believe the collective way is the only way to really do something serious with specialty coffee. I don't think you know not caring about where the coffee comes from and not really delivering on the promise of what you pay to the farmers and trying to squeeze money out of yourself to give to farmers. I think if you're not doing that, I don't think it is actually sustainable. And I think in coffee, yes, the market price is very much dependent on the regular supply-demand mechanisms. How much coffee do Vietnam and Brazil produce in a given year? And so there are mechanisms we can't do anything about, but we can do a big thing about the market that we are in; in the specialty coffee market. And I think with transparency is that you know yes we are only buying you know a relatively small amount of coffee even for the Danish consumer market, but by putting transparency on the top of the agenda, I think we can create a ripple effect. We can get people to ask questions and the more people become aware of it, the more people who listen to this podcast for example and start thinking about it will go out into the supermarket and look at the retail shelves and see you know this is a tempting offer of four bags of coffee for 100 Kronors. I saw my local supermarket had it on the other day and it's just for me it's appalling. It's at a price we're looking at that coffee, and no there's no possible way that has been beneficial for the farmers. They have not made money on that coffee. They have most likely lost money producing that coffee, but so it's basically like modern slavery. And the supermarkets are doing it because they can take the hit they will lure people in with the big offer, and they will hopefully buy a lot of other groceries, but it's just not sustainable. And so hopefully, through our actions, we can provoke, disrupt a little bit. We can get people to think about their actions and how it transfers into real action on a bigger level.

Silja: So it's also about creating a new norm?

Klaus: Yeah, a new norm and a way of … also for our industry like in specialty coffee I mean there's as you mentioned: There are so many new roasteries; so many coffee shops opening up in Copenhagen and a lot of them are doing great work; doing great branding. Their shops are looking amazingly beautiful. But I think just like you as a consumer by now expect latte art in your cappuccino; you expect baristas to know how to foam milk. I hope that we can push consumers to expect that people will be transparent and expect that they will provide what value did they really bring back. And if they can't, I would love consumers to take action saying well I'm not going to buy my coffee from you. Your shop looks nice on the surface. Everything looks like you're doing the right thing, but if you can't actually back it up, this is just as important for me as the latte art or whatever else.

Simon: And if you zoom out a little bit and think about changing industries I think there's maybe two actual ways to do it. One way to do it is to become a lighthouse and become like a good example of how to do it and let people know of it and kind of hope for others to be inspired. And the other way would be through scale, right? Scale that model, so you can show by numbers that it works. And others get drawn into it if they want it or not.

Klaus: Yes.

Simon: Where we would you see yourself on that scale?

Klaus: We are definitely the first one, the beacon of transparency. And there's something that also has, and I think that's also part of why we get the international orders because people know us for this and we give like, Peter especially, one of my co-founders and CEO of the company has recently spent the last two years working on an organization called transparent trade. And he's basically been one of the driving forces behind what is called The Pledge which is a pledge that we got 15 rostaries to sign in terms of pledging that we will provide full transparency that we will not you know just have a couple of showcase coffees but also say if it wasn't bought directly. Then we will say exactly how much wasn't bought directly. So you can't mask anything and be peer-reviewed. And as soon as that pledge launched which is about a month ago, 15 other roasteries instantly joined and more and more are calling every week to say we want to be part of this. So that's where it gets really optimistic for me because you can see that through our actions we can inspire others and we can get all these other roasteries to take action and the more who will join, yeah, the bigger it will become in scale as well. I also, or we believe that in our company I mean we will never be the new Starbucks. We have no ambitions for that, but we also have more ambitions than just being small and in Copenhagen. I really think that and this goes back to all the investments we've done internally in the company in the last years that we can see that we can grow the company. So this is why it means so much to me to hear you say that you can see that level of consistency now just because that is exactly what we can do and we can see by growing we can actually invest more into the quality. Suddenly we can provide more training for our staff. Now we have besides our really rigorous training that we do in the beginning we have workshops almost every month for staff members that are you know we pay them to come in for long sometimes half a day, sometimes full-day workshops where we work on different aspects of coffee. And again sometimes it can be something that provides some more knowledge about what happens at the farm level. Other times it can be focusing on how do we provide exceptional service and what is service you know in the industry in general? What kind of level of service do they do at Michelin star restaurants? So taking all this that that excites people and that's stuff we can only do now that we have a certain scale and we have more money to put into those things. That wasn't possible when it was just the four of us.

Simon: How long do we have to wait until there's a first Coffee Collective outside of Denmark?

Klaus: I don't know. Still a while. I'd still say like we really feel at home in Copenhagen. But at some point, I'm sure we will open up something abroad. Just because it would make sense, it would be fun. I think as well for us to showcase it somewhere else. But there I don't know. It could be five years easily. We are very patient people as well. Like we don't have the ambitions to go out and say 500 coffee shops in five years or even ten within the next year. Like it's perfectly fine for us to open one and then take a little breather, let that grow to make sure people are founded and make sure we have it with the quality. And then we can start looking for a new place.

Simon: And that's also possible, I think because you're a 100% self-owned, right? Because there's no one standing in the back door and saying "hey, deliver!"

Klaus: Absolutely. And that was a big part when we started. We had actually people who were willing to invest in us, and we decided that we didn't want that. It meant that we had to you know borrow money in the bank at you know really bad rates and you know we had to our small shitty apartments you know take loans in those and so on and but it really meant that we knew that down the line we didn't want the risk of having an investor who would say "ah you, shouldn't pay that much for this coffee, we'd rather see some profit now". We can say we care about – ehhh … what is the word? Profit. You see, I don't even know the word.

Simon: Symbolic.

Klaus: Yeah, the only reason we care about profit is that it shows if we are doing a healthy business. It shows that we're on the right track and we're not being and …

Silja: And you can pay the farmers better.

Klaus: And we can pay the farmers better. And that's again where we show the beacon: We can actually run a profitable, sustainable company while paying some of the highest prices that anybody in the world pays for coffee. We can be transparent about it. We can have you know union agreement for our baristas as one of the only coffee shops. We can do all these things and actually make a profit. It also means we don't pay ourselves the highest salary or our workers. I mean, I would like to pay them even more. We are at a good level, but I mean nobody here comes into our company expecting to get rich. It's not like they see it and think "ok this is what's gonna buy me a Porsche". But at the same time, we really think it's amazing to be able to have built a company that's been profitable every year. It's only the first year of our company where we didn't make a profit. And at that time we were close to being bankrupt, but we really didn't pay ourselves a salary for like half a year and then scratches together. And since then I think we have that backbone of knowing: It can take some effort, but it can actually work out.

Simon: Thank you so much for listening. If you enjoyed this episode and would like to know more, head over to www.theidealist.co! As always, there's one more thing we ask our guests, which is: Who should we talk to next?

Klaus: Oh, man! There's so many. Copenhagen is just filled with so many super interesting people. One of my good friends and a person that I find continuously inspirational is Christian Puglisi, who has a restaurant Relæ. We became good friends when he moved into Jægersborggade after we'd been there for a couple of years and just really hit it off. He's inspirational because he has the same kind of approach that is … I mean, yes, he runs a profitable business. His chain of now also four different restaurants and we have four different coffee shops. They are profitable as one of the few Michelin star restaurants. At the same time as being super hardcore on going all organic on everything, they get in the door; not just 90%, but every single thing. And he keeps really pushing things. So if I had to name one, it would be him.

📷 Coffee Collective

"Just like you as a consumer by now expect latte art in your cappuccino; you expect baristas to know how to foam milk. I hope that we can push consumers to expect that people will be transparent. And if they can’t, I would love consumers to take action and say: Well I’m not gonna buy my coffee from you."

— Klaus Thomsen [00:34:33]

-

14 Frances Shoemack

Abel

-

13 Rob Wijnberg

The Correspondent

-

12 Matt Orlando

Amass Restaurant

-

11 Mihela Hladin Wolfe

Patagonia

-

10 Tuomas Toivonen

Holvi

-

9 Jan Vapaavuori

City of Helsinki

-

8 Carel Neuberg

Marie-Stella-Maris

-

7 Mariah Mansvelt Beck

Yoni

-

6 Taco Carlier

VanMoof

-

5 Nathan Gilbert

B Lab Europe

-

4 Klaus Thomsen

Coffee Collective

-

3 Henrik Marstrand

Mater

-

2 Maximilian Strecker

Consortium Purpose

-

1 Christian Paul Kägi

QWSTION